|

|

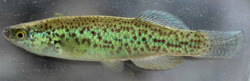

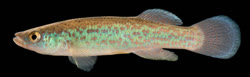

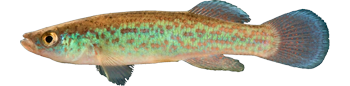

Due to its restricted range and its specific habitat requirements, the Barrens Topminnow (Fundulus julisia) is constantly teetering on the brink of extinction. They are only found in a handful of locations in Middle Tennessee where they can inhabit springs and creeks but seem to prefer shallow, light-filled pools that are heavily vegetated (they cast their eggs into watercress and filamentous algae). Unfortunately it is the dewatering of these habitats caused by drought, stream diversions, and irrigation withdrawals that make them uninhabitable to Barrens Topminnows either intermittently or permanently (in the case of the Duck River population’s apparent extirpation). Perhaps the greatest threat to the long-term survival of this species is the invasion of the nonnative Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), which have been implicated in out-competing and replacing Barrens Topminnows in their specialized habitat. During the most recent drought last fall, some of the pools that Barrens Topminnows populations were relying on had dwindled to mere puddles; this spurred a multi-agency effort to go and rescue remaining individuals before it was too late. My friend Dr. Bernie Kuhajda said of the event: “I thought it’d be dry. I had no idea there’d be practically no water here. I don’t have a lot of hope. This was by far the healthiest population of Barrens Topminnows anywhere. This is pretty cataclysmic.” This is the reality that, in order keep this and many other threatened and endangered freshwater fish in the American Southeast alive, it requires intensive management efforts. But it’s worth it; these species have survived for many thousands of years as our own species simultaneously became a master of evolution. My friends at Conservation Fisheries have been maintaining arks and actively propagating three separate (genetically distinct) populations of Barrens Topminnows since the mid-1980s. CFI co-founder and friend Patrick Rakes even wrote his 1989 masters thesis on this beautiful fish. - Todd Amacker

|